I don't remember exactly when it happened for me, but the thought arose with surprising clarity: something is deeply wrong with the United States, and I don't want to live here anymore.

When I tell people this, they nod knowingly and say something about the 2016 election. While that critical turning point sped up my timetable, the realization that something fundamental was off in the country of my birth actually began years before that.

When I met Robert (now my husband) in 2015, I became a beneficiary of his love affair with Italy. Though I was well-traveled and had been to Italy a few times, I had never really gotten to know people who lived there. Through many visits and conversations with Robert's friends in Italy, who became my friends, my nascent belief that it might be time to leave the U.S. slowly solidified until it became almost the only thing I could think about.

I began to notice a learned helplessness in the United States, where people don't revolt at the notion of a college education costing hundreds of thousands of dollars. I wondered why so many people treat it as completely normal that we have GoFundMe campaigns to help people pay for life-saving medical care that their health insurance won't cover.

I watched as people on social media claimed it was "pro-labor" to tip a person for ringing up your order at a food or coffee chain rather than demanding the multi-millionaire (or billionaire) owner of that company pay their employees a living wage (as is the norm in Europe, where tipping is not expected and the owners of the restaurants and stores are typically not among the uber-wealthy).

I realized there are other places in the world (not just Italy) where life isn't about conspicuous consumption and "crushing" and "killing" your life goals, where people aren't drowning in debt just to pay for basic life necessities. There are places where people have free time and where that free time is used to do things they love — not to start a side hustle.

I started to have a dawning awareness that we don't have to live this way.

I also began to notice how calm I felt in Italy for extended periods, even when working from there, so it wasn't due to being on vacation. I could feel my nervous system settle. I noticed how I began to find the famous Italian inefficiency charming. It was a kind of quiet rebuke to the productivity fetish in the United States, where businesses are forever trying to "optimize" and "streamline" to please their shareholders and enrich their CEOs while making life increasingly miserable for their employees.

"It really does change you from the inside out when you get to choose a life that serves you." Therapist Courtney Leak on leaving the US to make Panama her home

One turning point was a dinner with our friends Frances and Ed, who have lived in Italy for half the year for decades. They brought along an American friend who had moved from Brooklyn to Tuscany to open a hotel a decade prior. I asked if she ever considered returning to the United States.

She said no—she would never raise her son in the United States unless they changed the gun laws. She didn't want her child to be slaughtered at school by a lunatic gunman and listen to people chalk it up to the price you pay for “freedom,” as though people in other countries are not free because they can’t own an assault rifle.

Oh, right, this is not normal. We don't have to live like this.

She felt safe in Italy and didn't worry about her child going out to play the way parents in the U.S. do these days. She enjoyed the easy pace of life and connecting with the town's community, which gathered nightly to walk in the town square and casually socialize.

It sounded like a fairy tale.

Another clarifying moment occurred on a flight home from the 2016 New Hampshire primary. I was seated next to a Danish woman, a former mayor who was part of an international contingent observing American democracy in action.

People in Denmark are often ranked the happiest in the world. I asked her if this was true. She said she didn't know if they were the happiest, but that they were happy. She ascribed this to the fact that their basic needs were met. Nobody worried about running out of money for retirement or whether they could attend college or afford health care. Because education was free and life was affordable, people chose careers based on their passions rather than on earning potential. Yes, they paid 50% in taxes but didn't worry about having what they needed. Nobody graduated from college, saddled with the debt of a small nation.

"To show you how much the government thinks about how to serve the people, right now they are debating whether they should pay for women in nursing homes to have their hair done since it is part of their dignity," she told me. Older people are respected and cared for in Denmark in a way they are not in the United States.

Sounds so humane, I thought.

I couldn't imagine what it would be like to not worry about many of the things on her list.

While Denmark's government is more functional than some other European governments (including Italy), the view that people should have their basic needs taken care of is typical of the continent. What are considered "entitlements" in the United States are rightly understood as human rights in these countries.

I should note that there are other countries and continents to check out if Italy or Europe isn’t your flavor. My therapist moved to Panama after she found a group for Black expats on Facebook and discovered Panama would be a healthier and safer place to raise her son. I recently listened to the ‘Quitted’ podcast by

+ Holly Whitaker about a Black American woman moving to Grenada and found it extremely inspiring.Why Is Everything So Hard In the US?

In October 2019, Robert and I spent a month in Trieste, Italy, while he worked on an article for National Geographic featuring the storied Northern Italian port city.

I was extremely burnt out. I was in the thick of it at CNN, coming off two years of utter insanity in the US political world. It was exhausting and also frightening to contemplate what was becoming of the US.

On a more personal level, I was frustrated by the lack of meaningful friendships in Washington, DC, where we live. Everyone was hyper-busy, overworked, and stretched so thin that it was hard to find the energy and the time to have the kind of regular, causal connection that used to be commonplace, even in cities.

While in Trieste, I signed up to take one-on-one Pilates classes from an Italian woman in her late 30s. As I shared my frustrations about life in America, particularly how lonely it could feel, she asked me how often I saw my friends. "About once a week," I said, even though as I said it, I realized it was much less.

She was shocked. "This is not normal," she said. "I see my friends every day." She explained that when she left that evening, she would stop to see her friends as she walked home—a glass of wine with one, perhaps dinner with another.

None of this was planned in advance.

If you showed up at someone's house in Washington, DC, unannounced, you would be considered a sociopath. I am not exaggerating. Perhaps you could do this once, but if you did it more than once, people would think you were a problem.

In major US cities (where I’ve spent my adult life), getting time on the calendar to get together with friends resembles something akin to scheduling a space shuttle launch. I was very much feeling what

shared last week in The Friendship Problem: Why friendships have started to feel strikingly similar to admin. She writes:[I]t seems normal now that plans are made far in advance — scheduled around myriad travel and wedding weekends and kids and work commitments — and then canceled right before. Someone doesn't follow up or cancels and then never proposes an alternative plan. Similarly, promising new adult friendships never seem to blossom into the kind of quotidian check-ins and week-to-week ephemera that the friendship of our younger years is based on. Life-long friends make new life choices, drift apart. The friendship fizzles into WhatsApp volleys back and forth, and then someone doesn't answer the last message, and then it's a year before you ever talk again.

Perhaps people in smaller U.S. towns can still drop in on friends and don’t spend half their lives planning get togethers. (Let me know in the comments).

But Trieste is not a small town in either size or demeanor. It's a sophisticated, literary, and cultured city of around 200,000 people, filled with ancient architecture and fine dining. It's a stone's throw from Venice to the west and is the capital of Friuli Venezia-Giulia, one of the best white wine regions in the world.

No city like this in the United States exists where people—including Pilates teachers—are not hyper-busy and burnt out. Actually, there is no city in the U.S. like Trieste, period, but that's for another essay.

A few days before we flew back to the U.S. from Italy, we saw our friends Frances and Ed for dinner. I was not much fun, as I had I developed a throbbing pain in my jaw. I found out when I got home a few days later that I needed a root canal and was unceremoniously handed a bill for $5000. It would be hard to overstate my shock. Insurance didn't cover this, so I had to pay out of pocket.

This was a big financial hit, and I was well paid. How could the average person afford this? They can't, which is why so many people get trapped in medical debt after being forced to put critical care on a credit card.

Ed told me later that he had the best root canal of his life in Italy, costing $500. On our most recent visit to Puglia, we met a very successful Italian dentist at a dinner party, and he said he would charge around 250 Euros for that service. I have heard many stories like this about other types of medical care in Italy.

There is no reason there should be such a wide discrepancy between prices for the same service in Italy and the United States. The same is true of health insurance—I could buy a year's worth of health insurance in Italy that would be lower than my monthly premium in the United States.

And no, the U.S. is not more expensive because it has a better system. There are many things that Americans have been brainwashed about, but nothing comes close to the sacred delusion that the U.S. has "the best health care system in the world" ™ and that Western Europe is some backwater of substandard care.

But it's more than just that health care and education are affordable in Italy. It's that everything is more affordable than in the U.S.. Life in the United States keeps getting increasingly expensive to a point that simply doesn't make sense.

On the trip we just took to Puglia, produce from the grocery store and farmers markets—which was vastly superior to anything you get in the U.S.—was a third of the price of what we pay in Washington, DC.

Then there is cost of owning a home in the United States. As The Atlantic noted this week: It Will Never Be a Good Time to Buy a House:

The Case-Shiller index of home prices sits near its highest-ever inflation-adjusted level; houses are unaffordable for middle-class families across the country. Rural areas are expensive. Suburbs are expensive. Cities are absurdly expensive. Nowhere is cheap. That's in part thanks to mortgage rates. The monthly payment on a new home has increased by more than 50 percent in the past three years, as 30-year mortgage rates have climbed from less than 3 percent to nearly 8 percent.

We experienced this firsthand when we considered where we might move in the United States to find a more sane and affordable life so that we could work less and have more time for friends, family, and life in general.

Any place remotely desirable to us was out of our price range, and we are two successful professionals with no children. It’s not just that houses everywhere are expensive and interest rates are high. It’s that these houses are delusionally overpriced. Even if I had the money, I would not pay a million dollars (or more) to live in homes that pre-COVID were selling for $450,000.

Capitalism Has Gone Off The Rails

When I was growing up, the United States was a capitalistic country, but there were guardrails. They were not necessarily explicit, but they were understood to exist. Those guardrails are gone.

Call it hyper-capitalism or late-stage capitalism, or whatever you want: there is no longer even the slightest sense of decency.

Now there is no shame in making 800 million times more than your average worker at your company, who you would lay off in a heartbeat if it were to your financial benefit—in fact, these people are often glorified as the epitome of the American Dream.

While American workers have become more productive, none of the benefits of this productively accrue to them. In theory, increased productivity due to technological advances was supposed to lead to less work because work could be done more efficiently. But in the United States, the opposite has happened. Americans work more than they ever have—and more than their peers in other industrialized countries—and with less employer support than in the past.

The only people working less are the super wealthy, who live in a way almost comically disconnected from the average American’s existence. The New York Times ran a story recently about super-rich New Yorkers:

Although everyday life has become increasingly unaffordable for almost everyone, a new class of private, members-only and concierge services is emerging [in New York City].

Ultraexclusive clubs, laundry specialists, on-demand helicopter rides and services that allow users to bid hundreds of dollars for a restaurant reservation are transforming how those with lots of disposable income eat dinner, work out, see the doctor, look after their children, walk their dogs and get around — all without really having to interact with hoi polloi.

Meanwhile, the rest of America is drowning in credit card debt and running their bodies into the ground, chasing success and stability. Because everything is so expensive and our hyper-capitalist culture tells you your value and happiness are derived from your level of career accomplishment and acquisition of material goods, it starts to almost make sense that people would work so hard to achieve this identity for themselves.

Even if a person is enlightened enough to reject the consumerist rat race, they still live in a country with almost no social safety net and a Hunger Games mentality, which means they are going to have to work a lot just to survive, especially because the days of jobs with great benefits from pensions to health care are pretty much over. (Again, the lack of decency).

When Prioritizing Your Mental Health Means Leaving the U.S.: Why radio host, author and MSNBC commentator Zerlina Maxwell is moving to Italy

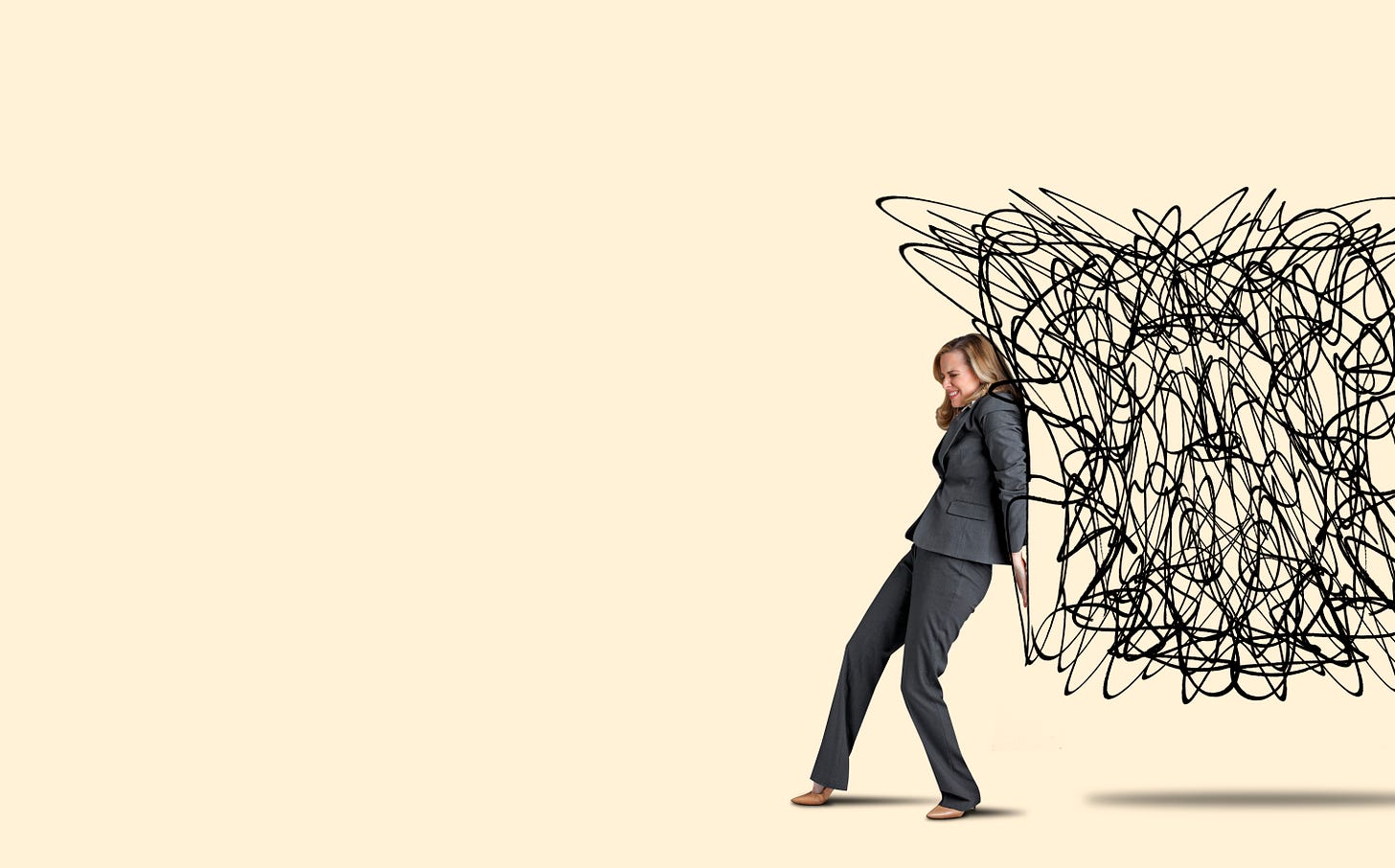

This kind of pressure inevitably leads people to overwork and eventually burn out.

breaks it down:In short, burnout is caused by 1) problems on the societal level (lack of social safety net, precarity, dealing with being a person in your particular body with your particular identity in the world); 2) problems at the level of the workplace (policies, norms, work culture, productivity expectations); but also 3) problems on the level of the individual (self-value derived exclusively through work, inability to adhere to guardrails against overwork set by yourself and others, obsession with micro-management).

On the other side of burnout, you discover you got the opposite of what you were promised. The more we acquire, the more we achieve, the less happy we are. Only now, you also have the problem of cratering mental health and often some sort of chronic illness. We are not designed to live this way, and our bodies are here to remind us of this fact. (If you doubt this, I highly recommend Gabor Mate's latest book, The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness & Healing In A Toxic Culture)

Eventually, all your "hustle and grinding" leads you to the land of "self-care."

Self-care is late-stage capitalism’s solution to the problem it created. How convenient that after turning your neck into a tangle of knots or creating pathological levels of anxiety and exhaustion, the "solution" is for you to spend money you don't have so you can just feel normal.

A whole industry has sprung up to patch up your broken body, mind, and soul just enough for you to keep playing this sick game where you never get to rest, have a hobby or spend unscheduled time with friends or family, or just live an everyday life.

Self-care does not fundamentally change anything; it is a band-aid. A bath bomb, essential oils, a meditation app or a Thai massage will not fix your problems. This is not to say that they can't bring temporary relief. But as

says, “You can’t meditate your way out of a 40-hour-workweek with no childcare.”We need something radically different. What most of us need is healing—and a completely different way of living. We need structural changes to how we live in the United States.

Until then, I’ll be healing in Italy.

Robert and I always joke about how hard it is to find a good massage in Italy unless you are in a major city. By that, I mean a massage the way the average American thinks of massage: a person beating the crap out of you to break up the snarl of stress that has made a home in your body. In Italy, they still treat massages the way we used to: as a luxury, not essential health care. I'll often come back from getting a massage there to report that the person basically just rubbed lotion on my body, which is apparently all the average Italian body needs.

This is not to say that chronic stress has not found its way to Italy—I think that, like all American inventions, the hyper-capitalist mindset that drives so much of our misery is currently being exported around the world. I recently spoke with an Italian woman who experienced extreme burnout while working in Milan.

The part of Italy we have settled on is not near one of Italy's major metropolitan cities, so it will be a long while before burnout culture reaches it (if it ever does). It's called Puglia, which is in the south in the heel of the boot. We made an offer (that was accepted!) on 6 acres1 of land close to a cluster of lovely historic towns and about an hour from the bigger city of Lecce. It's a 25-minute drive to world-class beaches with clear blue water and white sand.

The land is covered in olive trees alongside almond, chestnut, pear, pomegranate, and apricot trees. Wild tomatoes, artichokes, rosemary, bay leaves, and capers grow there. You can have a vegetable garden year-round.

Our plan is to build a small house with a one-bedroom guest house and enough outdoor space to host retreats. I can't imagine how we could ever afford anything like this in the United States.2

Even if we could, I would still choose Italy because it's not just a place but a way of life.

I want to learn how to live differently.

I want our land to be a place of healing and becoming whole. I want it to be not just a place that patches people up and sends them back on the field to get beat up again, but helps people see that life can be different and they deserve more than the thin gruel currently served up as the “American Dream.”

Still: I Can’t Quit You, America

While it may seem I have given up on the United States, I have not.

Partly, I am still tethered to living here at least part of the time because my husband's job requires him to live in DC. But even if eventually when we are able to live in Italy year-round3—I plan to move there the end of 2024—what happens to and in the United States will always matter to me.

It's not just important to me personally that the US survives and thrives. It's essential to the world that this young (and incredibly immature) nation grows up and lives up to its claims and promises about what it is.

I have not stopped believing this is possible, and I never will.

The thing I love the most about the US is the one thing I can think of that is missing in Italy: diversity. I believe that everything that is good and right about the United States is a direct result of our culture being not just the culture of one people but of many.

I'll end with this quote from Barack Obama in his 2020 book A Promised Land that I think says it all:

“And so the world watches America—the only great power in history made up of people from every corner of the planet, comprising every race and faith and cultural practice—to see if our experiment in democracy can work. To see if we can do what no other nation has ever done. To see if we can actually live up to the meaning of our creed.”

Related

This previously stated “ten” acres, but we ultimately decided to just buy six, so I’ve updated it.

We were lucky to be connected with the wonderful Karina Prasad, who helped us find the land and navigate the process of purchasing it. Karina is an American who has lived in Europe for most of her adult life and now does project management here in Puglia with an incredible team of Puglians. If you are interested in moving to this area and renovating or building, I highly recommend her. You can send an inquiry to her team at enquire@gelsobian.co. If you are interested in finding an already done property to purchase or rent, I suggest Michele Torroni, who was the agent who sold us the land. Michele grew up in Puglia and lived abroad for a long time as an adult and speaks perfect English (and many other languages I think). He can be reached at micheletorroni7@gmail.com. Feel free to mention to Karina or Michele that you found them through this publication.

I deleted the information about double taxation because it looks like because the US has a tax treaty with Italy we will not be subject to double taxation. I also changed “if” to “when” we are able to live in Italy because I am moving there the end of 2024 and my husband will come when he retires in a few years.

So many people feel what you feel. I cringe when I hear people refer to the US as “the leader of the free world.”

I don’t disagree with the things you said. On the other hand, my guess is that your experience reflects the high-powered world of a person with a really high-level job in a city known for off-the-charts crazy.

I’ve been a “regular” at coffee shops in Baltimore for several decades. When I worked full-time at a non-high-powered-job, I stopped an hour before work to have a coffee and read the paper. There were others like me there. We got to know each other. We noticed if someone was unexpectedly away for a few days. I went on a date with one of the regulars. Just one, ha ha.

Now I work part-time, teaching qigong. I live with my partner, a man from India. He’s a psychiatrist with his own practice. Since the pandemic, he’s worked at home. He doesn’t make the money we think of when we think of doctors because of the way he chooses to work--not all about meds, taking patients who aren’t always able to pay, etc.

I teach on Zoom at home and in person a few places. Every morning, early, I go to a coffee shop in my community, where I actually have made friends. We linger over coffee and know each other well.

I live in an apartment complex in northwest Baltimore in a beautiful old neighborhood. We haven’t been able to get the money together for a house, and I do worry about old age. Yes I do.

When your job is thinking and reading and writing about the horrendous injustice and imbalance in our world, and there’s so much pressure to perform well, yes, for sure, you’re experiencing a way different life.

I do read a lot about the bad stuff, and I watch some cable news every day. But I also stare out my sliding glass door and look at the woods my apartment faces. I have a hummingbird feeder that gets a lot of action every summer. In the past month, I took a picture every day of the maple tree by my balcony. Full green, then yellow, then gold, then brown, then bare.

I live a privileged life. I also have worries and hard times, big and small. I cared for my mother, who had Alzheimer’s, for several years, which got more and more challenging and also frustrating because Medicare covers nothing Alzheimer’s-related until it’s time for hospice. Imagine, a brain disease not worthy of some help until the very end.

I read about the wars in the world and see the images and feel sadness and anger.

This is a snapshot of a life lived on a scale very different from the one you’ve been having.

Congratulations on making that big decision!

KP-you could write the instruction manual on my oven and I’d read it—you are truly THAT good! This however feels like a download of so many of our conversations and so many things I am nowhere near as articulate as you to express. We do many things right here in the US and it will always be home and I will always want our success! However, the shift in body, mind, soul in Italy can not be ignored and I don’t think that’s just because my last name ends in a vowel. We lack connectivity and are starving for it here and have adapted to the lowest denominator of it—texting, video chats and Instagram comments. I can not wait to see your property, your homeS, your dreams fulfilled (your’s, Robert’s and Lucy’s!). This piece was a masterpiece—Grazie per tutti. (And you can ALWAYS just walk in my house with FULL refrigerator privileges) Brava, Bella😘